This was a key driving question in my PhD research called “Dysfunctional breathing: its parameters, measurement and clinical relevance”. The real practical aim of my research was to create a standardised protocol for the assessment and treatment of dysfunctional breathing. I knew from my training and clinical experience as an osteopath that it’s not possible to assess or treat any condition well until you understand its characteristics and parameters well enough to define it.

So firstly let’s consider the question “What is functional breathing?”

The conclusion I came to is that functional breathing is breathing that most efficiently performs its various functions taking into accounts the circumstances and condition of the patient.

Next question “What are the functions of breathing?”

This is an interesting question that gets more interesting the more one thinks about it because breathing has both primary and secondary functions. The primary functions of breathing are the ones that are essential for keeping us alive and the secondary functions of breathing are more about how breathing interacts with other body systems in ways that help to maintain homeostasis and health.

The primary functions of breathing are:

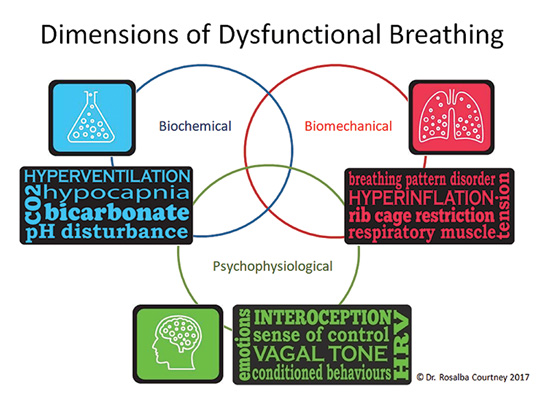

- biochemical and

- biomechanical

The biochemical function of breathing has to do with the regulation of oxygen, carbon dioxide and the pH of the body.

The biomechanical function of breathing relates to the action of the respiratory pump, the efficiency of which is dependent on the actions of the respiratory muscles, the function of the rib cage and habits and patterns of breathing.

The secondary functions of breathing refers to the involvement of breathing in things such as:

- Self-regulation ie calming and dealing with stress or improving mental focus, mindfulness and attention.

- Static and dynamic posture, spinal ‘core’ stability and motor control.

- Modulation and support of speech, vocalisation and upper airway function during daytime and night time breathing.

- Creation of rhythms or oscillations that allow systems to communicate and function together.

- Regulation of fluid dynamics eg in cerebrospinal fluid, lymphatic circulation, venous return to the heart and blood pressure regulation.

The efficiency of these secondary functions of breathing is reduced when the primary functions of breathing are not well maintained. For example, people with hyperventilation (a condition that results in low levels of CO2 and pH disruption) or neuromuscular breathing pattern disorders often find the sensations of breathing uncomfortable and unpleasant. For these people practising mindful attention to the breath or attempting to control the breath in ways that are supposed to be calming makes them feel more agitated and even distressed.

Functional breathing has EAARS – I created the EAARS acronym as one way to think about whether a person’s breathing is functional.

EAARS stands for –

- Efficient,

- Adaptive,

- Appropriate,

- Responsive and

- Supportive of heath.

The EAARS model acknowledges the dynamic, ever changing nature of healthy breathing and the fact that the way a person breaths may represent their best attempt to compensate for pathology or structural deficit or even psychological state.

Using the EAARS model to evaluate breathing functionality, we are concerned with how effectively the breath changes and responds to meet the body’s changing needs rather than just looking at static measures and textbook norms.

The EAARS model for evaluating functional and dysfunctional breathing takes us away from rigid ideas about optimal breathing and opens up possibilities for innovative ways of approaching breathing retraining that are respectful of the body’s own healing and compensation mechanisms.

Here is a letter by letter detailed description of the EAARS acronym.

Efficient breathing – Certain modes, rates, rhythms or patterns of breathing are more efficient than others but to accurately interpret the functionality of breathing we need to look at the whole picture. For example, generally speaking nasal breathing is more efficient than oral breathing at delivering oxygen. However there are situations where the upper airways are obstructed to the point when nasal breathing reduces oxygen and overloads the heart and mouth breathing is more efficient at maintaining oxygen levels and therefore more functional.

Adaptive and Appropriate – When a person’s breathing is functional it adapts to the changing conditions appropriately. Healthy people have breathing that changes all the time, sometimes it’s more regular, sometimes it’s less so, sometimes breathing is more thoracic and sometimes it’s more abdominal.

At the most basic level it helps to understand that functional breathing is breathing that adapts appropriately to activity and rest. At rest we should ventilate much less than during physical activity or during arousal. When breathing does not adapt to the condition of rest we might find that the person’s breathing is beyond their metabolic requirements (giving low CO2 – hyperventilation) or that their breathing pattern stays in the active upper thoracic configuration and does not move to the relaxed abdominal configuration when they are in a position of rest.

Responsive – Because functional breathing is adaptive, over-control and excessive preoccupation with one’s breathing can make it dysfunctional. Rigid ideas about what optimal breathing looks like eg always abdominal, always gentle and soft etc can make it dysfunctional.

Supportive of Health – Breathing interacts with most body systems in a two way relationship. Healthy functional breathing promotes virtuous cycles that maintain homeostasis.

So what is “Dysfunctional Breathing”?

In a nutshell dysfunctional breathing doesn’t have EAARS, it’s not efficient, adaptive, appropriate, responsive or supportive of health. It produces symptoms and contributes to vicious cycles of pathology and dysfunction in other body systems.

Another conclusion from my research is that dysfunctional breathing is multi-dimensional in 3 key dimensions: biochemical, biomechanical and psychophysiological. People with dysfunctional breathing can have dysfunction in one or several of these dimensions. Targeted treatment that’s based on accurate evaluation of each of these dimensions is the key to effective treatment of dysfunctional breathing.

I developed the multidimensional model of dysfunctional breathing and the EAARS model of breathing functionality as the guiding principles of what I call Integrative Breathing Therapy.

If you want to know more about the validated assessment and treatment tools of Integrative Breathing Therapy please consider taking my one-day course. Details here:

https://www.rosalbacourtney.com/intro-to-integrative-breathing-therapy-1-day/

Further Reading

- Boulding, R., et al., Dysfunctional breathing: a review of the literature and proposal for classification. Eur Respir Rev, 2016. 25(141): p. 287-94.

- Courtney, R., Strengths, Weaknesses and Possibilities of the Buteyko Method. Biofeedback, 2008. 36(2): p. 59-63.

- Courtney, R., Functions and dysfunctions of breathing and their relationship to breathing therapy. International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine, 2009. 12: p. 78-85.

- Courtney, R., Dysfunctional Breathing: Its Parameters, Measurement and Relevance, in School of Health Sciences. 2011, RMIT: Melbourne. p. 315.

- Courtney, R., Questionnaires and manual methods for assessing breathing dysfunction, in Recongizing and Treating Breathing Disorders, B. Chaitow, Gilbert, Editor. 2014, Elsevier: London.

- Courtney, R., Breathing training for dysfunctional breathing in asthma: taking a multidimensional approach. European Respiratory Journal Open Research, 2017. 3(4): p. 00065-2017.

- Courtney, R., A Multi-Dimensional Model of Dysfunctional Breathing and Integrative Breathing Therapy – Commentary on The functions of Breathing and Its Dysfunctions and Their Relationship to Breathing Therapy. J Yoga Phys Ther, 2016. 6(257).

- Courtney, R., Management of Respiratory Dysfunction, in Textbook of Osteopathic Medicine, C. Standon and J. Mayer, Editors. 2018, Urban and Fischer.